A Time to Improvise.

Performance in Post-Soviet Russia

Before then the history of private initiative in the theater had been rather sad or anecdotal. In the early 1980s, my friends wanted to open an Orange Theater. Orange is a fun color. But just at that time, in a certain African country, which was supported by the USSR, there happened to be a coup d'état. To a great misfortune, the country’s flag was orange. Fearing "anti-Sovietism," the Party and Komsomol officials on whom the decision depended refused permission to open the theater.

But then came the 1990s, and all colors of the rainbow became possible. The state lacked money for culture, and private initiative flourished. The borders had opened in the late 1980s, and artists the Soviet public had never seen before came to visit. Audiences in Russia, long accustomed to a diet of classical ballet, the Young Communists pageants, and Russian folk ensembles had their first glimpse of contemporary dance. People felt the breath of freedom, as they had done when Isadora Duncan came to Russia at the start of the 20th century. Her dance, which appeared "natural" and improvised, deeply shocked the public: "So it’s really possible to dance like that?! Not in ballet positions, not en pointe, not expressing conventional theatrical emotions, but your own, sometimes conflicting feelings?!" The revelation offered by Duncan’s performance in the beginning of the century set off a country-wide boom in modern dance, which lasted through the 1920s. After Stalin’s "Great Turn" and the cultural repressions that accompanied it, all unofficial initiatives in theater and dance were prohibited, and modern dance only came back to us from abroad at the turn of the 1990s. It was a time for physical theater, performance, contact improvisation, alternative fashion shows, and a range of other shows, most of them done on a shoestring, but carried off with immense creative energy.

Soviet official discourse had devalued the word. Language had ceased to be a means of revealing truth and instead had become a way of concealing it, of not saying too much. This was the "newspeak" ridiculed by George Orwell. The loss of confidence in official speech entailed a search for a new language that was physical and not verbal. Pantomime had already significantly developed during the so-called "stagnation years" of Leonid Brezhnev’s rule. Modris Tennyson in Riga, Giedrius Matskyavichyus in Kaunas and Moscow, Nail Ibragimov in Kazan and many others created a theater of pantomime, or "plastic theater," which made statements of the utmost clarity without the use of words (I remember my own amazement at how this could be possible when watching a performance by Matskyavichyus).

Like the eroded reliefs on old coins, words had lost their power, and many found alternative means of expression in physical theatre and improvisational dance performance. First in the capitals (Moscow and St. Petersburg) and then in the provinces, a circle of people came into being who investigated different approaches to non-verbal theater. Marina Russkikh joined the Other Dance group, which brought together performers who were interested in modern dance and other alternative, "strange" dance formsⓘ. Other Dance held a festival at two cultural centers in St. Petersburg, and two performers, Natalia and Vadim Kasparov, set up one of the first Russian modern and contemporary dance schools, called Cannon Dance, at one of these centers. The Kasparovs also inaugurated the Open Look international dance festival.

The growth of the alternative theater community was helped by information about what was happening abroad, obtained with difficulty and not always first-hand. In the 1980s, foreign contemporary dance troupes began to visit Russia. Pina Bausch’s Rite of Spring was performed in Moscow, and Soviet ballet connoisseurs were aghast to see ordinary earth scattered across the stage. At the end of the decade, the Leningrad dancer Alexander Kukin watched a performance by a Western modern dance troupe and was struck by the aesthetics of movement freed from ballet canons and clichés. In 1990, Kukin founded his own dance theater, which still exists today. Director Anatoly Vasiliev implanted Japanese modern dance (butoh) in Moscow and his dancers travelled to Japan to visit dance guru, Min Tanaka, on his famous Body Weather Farm, where they practiced butoh and worked on the land. In Petersburg Natalia Zhestovskaya and Grigory Glazunov founded a theatre of butoh, which they called "OddDance."

M. Popova, “Spetsifika khudozhestvennykh strategiy v praktike sovremennogo tantsa Sankt-Peterburga s 1990-kh gg. na primere rabot Aleksandra Kukina, Ol’gi Sorokinoy, Mariny Russkikh i dr.” [The specifics of artistic strategies in the practice of contemporary dance in St. Petersburg since the 1990s on the example of the works of Alexander Kukin, Olga Sorokina, Marina Russkikh and others]. (Master’s dissertation: St. Petersburg, 2020), 91

Popova, “Strategiy v praktike sovremennogo tantsa Sankt-Peterburga,” 91

Popova, “Strategiy v praktike sovremennogo tantsa Sankt-Peterburga,” 95

Photo by Vera Dorn, courtesy of Grigory Glazunov and Natalia Zhestovskaya

As Sorokina recalls, this way of life was conducive to the development of contact improvisation. But there was more to that than bohemianism. Modern and contemporary dance and contact improvisation are techniques for achieving a physicality distinct from the taut, strong, eager, "ever-ready" body that was the Soviet dance paradigm. Modern dance began from this opposition to ballet and from a different, non-classical mode of body functioning. Ballet was focused on rigidly fixed positions, athleticism, and the muscular body, while the new dance cultivated free movement that aimed for naturalness. In ballet the body is elongated vertically, with a straight, stiff back, gathered and tense. Modern dance encourages the body to relax and be at rest without stopping the movement. The founders of the new form used new terms to describe it: Rudolph Laban spoke of an alternation between "tension" and "relaxation," Martha Graham contrasted "contraction" and "release," and Doris Humphrey referred to "fall" and "recovery."

The modern dancer intentionally plays with natural, physical forces, particularly with gravity. "Contact improvisation" is a concept that emerged among radical dancers in the United States in the 1970s. In this form of dance, the body is treated as weight, as a physical mass that interacts with and leans on the bodies of the dancer’s partners, obeying the natural forces of inertia and gravity. The rapprochement of the dancer’s body with the forces of nature aims to distance him or her from the artifice and conventions of stage dance (particularly ballet), liberating the dancer from normative body training ("sit up straight," "don't bend," "keep your hands still"), associated with the aristocratic ideal of the body, and aiding return to a natural, pristine, happy state.

Popova, “Strategiy v praktike sovremennogo tantsa Sankt-Peterburga,” 107

Popova, “Strategiy v praktike sovremennogo tantsa Sankt-Peterburga,” 107

Right: House in the Forest, Evgenia Andrianova

Photos by Sergei Panteleyev, courtesy of the author and Olga Sorokina.

Performers in both of Russia’s capitals were agreed on this approach. In February 1994, as Olga Sorokina recalls, "a series of high-octane events brought together and mixed the Moscow, St. Petersburg, and national theatrical crowds for a three-day carnival at the Rodina cinema in Moscow. It was followed by the Baby-dury (Women-fools) festival to celebrate Women’s Day on March 8, the Carnival festival in Moscow’s Manège building and Cook-Art in Tsarskoye Selo, outside St. Petersburg."ⓘ All of them were organized almost without money (according to Sorokina, sponsors threw in a few coppers and disappeared from sight), but creatively, improvisationally, and enjoyably.

The thematic content of early-1990s performances (assuming, for a moment, that in performance, form is separable from content) centered on protest against Soviet values, dismissal of everything official, and irony at the expense of socialist realism and other attributes of statehood. By the middle of the decade, the "against everything" theme had been done to death. Performance needed a new sense of purpose and mission.

Popova, “Strategiy v praktike sovremennogo tantsa Sankt-Peterburga,” 106

The ending of censorship and other Soviet prohibitions gave free rein to creative energy, and the idea of turning a performance into a ceremony, of endowing it with meaning and sanctity, was attractive to many. The anthropologist Victor Turner and performance theorist Richard Schechner had written in the early-1980s about the relationship between performance and ritual.ⓘ Modern studies of performative culture use concepts evoked by ethnographic study of the rituals of birth, initiation, and death, including liminal experience (states of transition, threshold experiences). A performance is considered successful if it enables the viewer to go beyond his or her ordinary sphere of experience, to sense transformation and spiritual change— in other words, if the performance is akin to a ritual.

"When the ordinary becomes conspicuous, when dichotomies collapse and things turn into their opposites, the spectators perceive the world as ‘enchanted'," writes performance theorist Erika Fischer-Lichte.ⓘ Her thought echoes the view of theater as transformation put forward by the early-twentieth century Russian playwright and director, Nikolai Evreinov.

Later, when irony over recently defunct Soviet culture had run its course and socialist realist art had become collectible, alternative performance began searching for new themes. What it found was something very old: the mythologemes of the old Slav world—figures of Russian folk mythology—and the deeply "national." That performance took this turn immediately after the years of reaction against Soviet ideology was perhaps natural, since the development of national themes had been frowned upon in Soviet times.

In the mid-1990s Ekaterina Ryzhikova and Alexander Lugin created the Sever (North) group, which laid the foundations of the "new archaic" art movement in Moscow. The name reflected geopolitical ideas that were becoming increasingly fashionable: the "North" was set in opposition to both the "barbaric South" and the "decadent West" as the bearer of true cultural values. The idea was to breathe new life into theater by combining playful costume performance and pagan myth, and to revive religious feeling. Before the creation of Sever, Ryzhikova made avant-garde costumes and participated in costume performances, where she "ironically combined archaic and techno, ethno-elements and a pseudo-industrial style."ⓘ

Sasha Kukin, “Choreographer’s page”, Sasha Kukin Dance Company, accessed July 3, 2021, http://www.kukin.spb.ru/en/about/choreographers-page.html.

Popova, “Strategiy v praktike sovremennogo tantsa Sankt-Peterburga,” 107

Richard Schechner, Performance Theory (London: Routledge, 1988)

Erika Fischer-Lichte, The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics, trans. Saskya Iris Jairn (Abingdon: Routledge, 2008), 180

Mikhail Buster, Elena Fedotova et al., Alternative Fashion before Glossies, 1985–1995. Moscow: Garage Museum of Contemporary Art, 2011. Exhibition catalog

Photo by Alexander Marov, courtesy of the author.

Photo by Alexander Marov, courtesy of the author.

Sever’s attempt to create a performance-rite and a performance-myth was welcomed by devotees of the Russian national spirit, and also by Andrei Bartenev, the acclaimed Russian artist, illustrator, and set designer, who named Sever his favorite theater group. While alternative dance performances took place mainly at festivals that were organized by the dancers themselves, performances by musical groups such as Sever and the costume performances organized by Bartenev took place mainly in clubs, squats, and galleries.

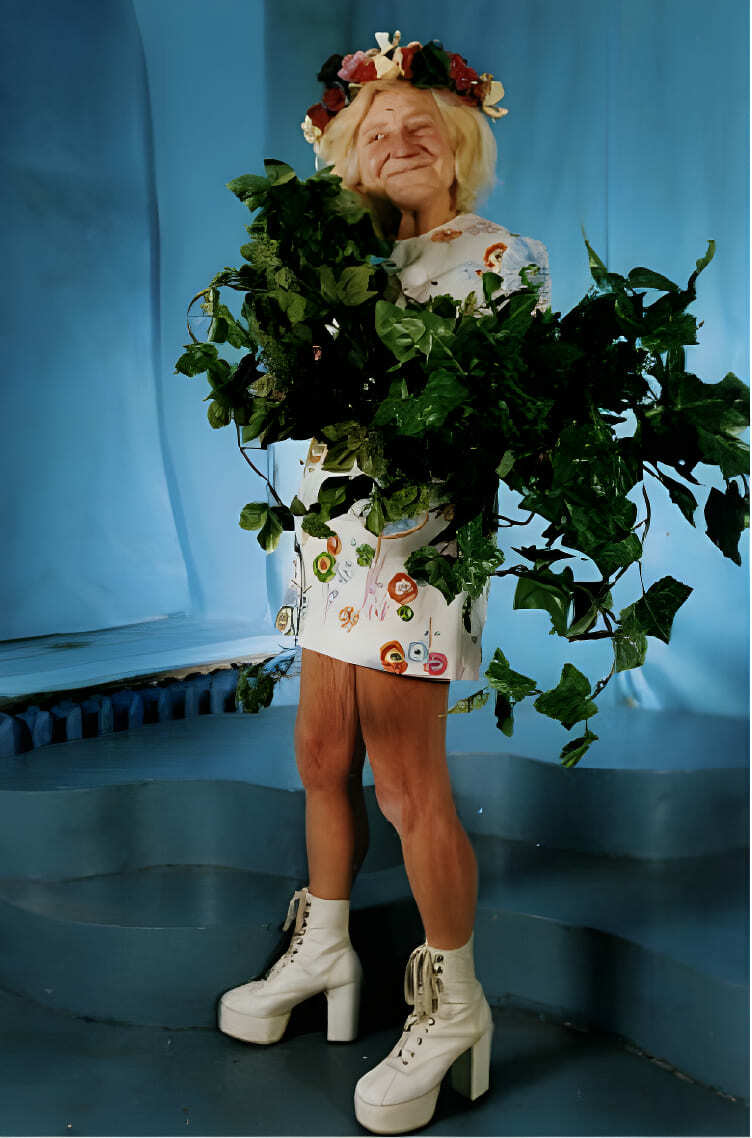

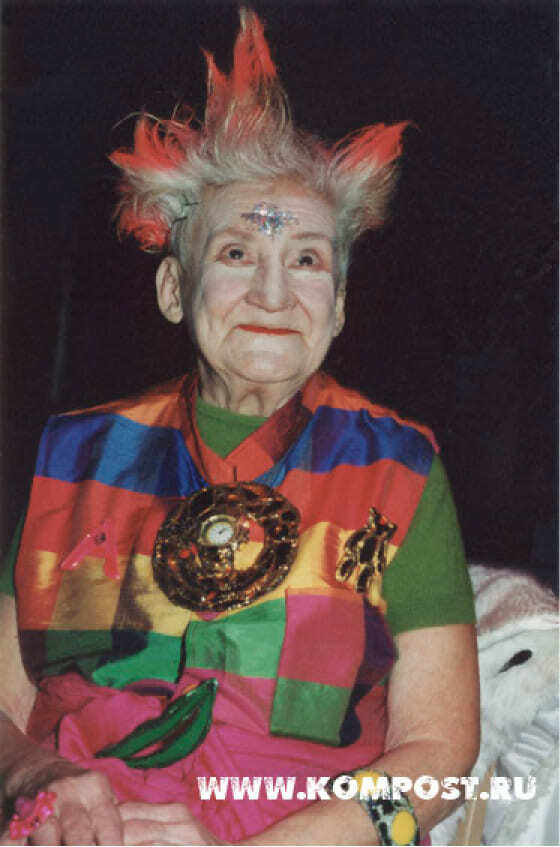

The "new dandy" and artist-performer Alexander Petlyura sought out treasures on flea markets, and staged impromptu catwalks in a city-center squat at 12 Petrovsky Boulevard, which became a center of Moscow’s 1990s underground culture, hosting workshops, concerts, and performances by Petlyura’s alternative fashion theater. The leading model at 12 Petrovsky was former actress Pani Bronya (Bronislava Anatolyevna Dubner) who was the only person officially registered at the address. She starred in Petlyura’s performance Snow Maidens Don’t Die and in 1998 won the Alternative Miss Universe prize at a competition in London together with Petlyura. The series of 12 collections entitled Empire in Things, created by Petlyura to reflect the styles of the decades of the twentieth century, has been called "the most unusual history of Russia" by subculture researcher Mikhail Buster.ⓘ

Mikhail Buster, Alternative Fashion, 54

The first nightclubs opened in Moscow at the same time as the first supermarkets and quickly became the most fashionable places to hang out through the night. By the middle of the decade, all of Russia’s big cities had clubs to suit every taste, with entertainment provided by drinks, stimulants, concerts, fashion shows, and performances. "The first clubs were opened by bohemians for themselves and those like them," writes Leonid Parfenov, "but in no time they drew everyone who was awake at night—the rich, the bandits, the foreigners, the young, and those who felt young. White Cockroach, opened by Irina and Alexei Papernykh, is really a communal apartment with a small stage. Svetlana Vickers' Hermitage is more spacious, but also conceptually poor… Bunker, Ne Bey Kopytom, and Manhattan Express offer different music and a different balance between live performance and DJs, but all of them are considered avant-garde, with the most advanced rhythms and ultra-performances by Masha Tsigal and Andrei Bartenev."ⓘ

In September 1993 Michael Jackson came to Russia for the first time. He gave a single concert at the Luzhniki Stadium, but his whole visit was a grandiose performance. Jackson’s stunts included stepping out with an army orchestra on Red Square dressed in a Russian officer’s uniform.

Andrei Bartenev, “Andrei Bartenev nakonets rasskazal vse o svoyem proshlom pri svidetelyakh” [Andrei Bartenev finally told all about his past before witnesses], Interviewrussia, February 17, 2012, http://www.interviewrussia.ru/art/andrey-bartenev-nakonec-rasskazal-vse-o-svoem-proshlom-pri-svidetelyah.

Leonid Parfenov, “Kluby” [Clubs], Proyekt “Namedni. Nasha Era” [The other day. Our era], https://namednibook.ru/kluby.html.

Sasha Obukhova, ed. Russian Performance 1910–2010. A Cartography of its History. Moscow: Garage, Museum of Contemporary Art, 2014. Exhibition catalog

Vladislav Mamyshev-Monroe, “Inteview,” Fraufluger.ru, November 3, 2011, http://www.fraufluger.ru/persons/vladislav_mamyishev-monro_krasota_v_izgnanii.htm. Politburo was the name for the commanding organ of the Communist party

Eggnog was Bartenev’s fitting farewell to a memorable decade and a nod to Russia’s new era of oil abundance. In his opinion the politics of galleries is most to blame for the fading of alternative performance by the end of the 1990s: galleries in search of grants began to focus on Western models and to support artists who imitated Western approaches.ⓘ The gentrification of galleries and clubs was also a factor. Performances ceased to parody officialdom, lost their improvisational characters, and turned into professional art. Abundance, fueled by rising oil prices, led to conservatism in politics and society. The new public, squandering easy money in clubs, wasn’t looking for social critique, but for entertainment, not for demythologization, but for the creation of a new myth. Club performances invented a different mythology—neoarchaism, technocarnival, and new dandyism, among others. From dance performance and alternative costumed shows of the 1990s a new genre, activist performance, was born and lived on in the streets and other public places, but more about that in another article.

Olga Vainshtein, “Sto igr na odnom litse: kostyumy i konteksty Andreya Barteneva” [A hundred games in one person: Costumes and contexts of Andrei Bartenev], Teoriya mody 56, no. 2 (2020): 115–143

Andrei Bartenev, “Na stile: Kak odevalis v 1991 godu?” [In style: how did they dress up in 1991?] (Public talk, Ostrov-91 Festival, Muzeon Summer Theater, Moscow, 20 August 2016)